Beg buttons as coal mine canaries

Recently, I was interviewed for a university class that combined psychology, public health and aging. I took the opportunity to consider these subjects through walkers, drivers and street design. This blog post is taken from that interview.

—Michael King

…or else!

My friend Sal failing miserably in his attempt to push the button. He blamed the fence.

Q - Canaries were often used in coal mines to detect oxygen levels. If a bird died from lack of oxygen, it was time to leave the mine. To continue the simile, what is a beg button and of what is it warning us?

A “beg button” is a button that one pushes to obtain a green signal at a traffic light. Some traffic signals are fixed time, meaning they change automatically. Some are activated, meaning they stay green for one direction until a user activates it for another direction.

Q - What is so wrong with traffic signals that one has to activate?

There is nothing inherently wrong with a system that requires activation. For example, most elevators have push buttons. Toilets flush upon activation (otherwise we waste water). Your phone has push buttons (for the virtual equivalent). I take issue with a system that subserviates a class of users - in this case people walking.

Let me digress to point out that I refer to people walking as people walking, not pedestrians. Many moons ago there was a movement to change how we speak about people with disabilities. Instead of words like handicapped and disabled, we shifted to people-first nomenclature. A person with a disability. A person walking slowly, not a slow walker. Synonyms for pedestrian include dull, plodding, and derivative.

Obnoxiously specific directions in Benbrook TX.

Another indication of how American driving society has failed its children, Boulder CO.

A parody of the Vision Zero campaign in Edmonton, Alberta and its focus on jaywalking. 46 people “jaywalking” were injured by drivers in 2016. This is 2/10 of a percent of the 24,702 crashes that year. From @newfangl3d.

Q - How do push buttons subserviate people walking?

Really by their very existence, and this is where I need to bring up the history of walking. Before the advent of motor vehicles (cars), there was really no need for defined rules of the road. Common law dictated walking on the right side, passing on the left, and yielding to those crossing and/or less abled. The next time you walk along a path in a park, pay attention to the unspoken rules people follow.

The onslaught of automobiles altered this relationship. 30 mph is 10x faster than 3 mph (walking speed). Streets became crash scenes, so governments began to regulate use. For reasons I won’t go into here drivers were privileged and the term “jaywalking” came into being. [Norton, Seo, Bronin & Shill]

The beg button is an outgrowth of this subjugation. Previously one crossed the “street” when and where one wanted, yielding to others and simultaneously being yielded to. The notion of “crossing the street” is ephemeral, as most were not paved, sidewalks were originally built to protect structures from storm and rain water, and people walked as they would. With new rules of the road, people were increasingly restricted to the sidewalks and crosswalks.

At the intersection of Main and Chestnut Streets in New Paltz NY, I once waited almost 3 minutes for the light to change. The signal is 3-phase, meaning one direction goes, followed by another, then a 3rd phase for people walking. There is a beg button, but if you push it at the wrong time, you have to wait until the signal cycles all the way around for you to get the light.

Q - I think I follow so far, but traffic signals keep us safe, no?

Actually, no. Traffic signals were invented to manage right-of-way at congested locations. Previously STOP/GO signs were used at crowded locations and times to manage railroads, horse-drawn carriages, trolleys, and people walking. When bicycles came along in the late 19th Century, they were lithe enough to move around and through crowds. The car changed this as they took up 37x more space per person (110 vs. 3 square feet). So when a vehicle stopped, it blocked. Cleveland had the first electric traffic signal in 1914. NYC had the first walking signal in 1934.

There are nine federal “warrants” for a traffic signal today. Only one relates to crash history, and the bar is very high: five injury or high cost crashes in the previous year. Fender benders don’t usually count. Traffic signals are about control, which is why the technical term is traffic control devices.

Q - But doesn’t a “walk” signal give power to the person walking? It gives them the right of way and tells the motor vehicles that they have to wait?

Only sorta. “The driver of a vehicle shall yield the right of way to any blind pedestrian carrying a visible white cane or accompanied by a guide dog.” [S11-511, Uniform Vehicle Code, 2000, these are the codes on which most state traffic laws are based.] Drivers are also meant to yield when turning - to oncoming traffic, people crossing the street, and so on. This is common law.

But traffic signals upend this relationship. Some refer to it as a “false sense of security”. When drivers have a green light, they reasonably assume the way is clear (cross-traffic has a red light). They don’t know whether the person in the crosswalk has a concurrent WALK signal, to whom they should yield. Right turns on red further strain this relationship. One could argue that signals should be red and yellow, never green.

At some signals, where there is no conflicting movements, say a midblock, then the WALK signal does provide power. Another example is a leading pedestrian interval where the WALK signal comes on before the green light. But otherwise WALK signals do not confer any special powers.

Q - It seems that signals are indicative at best. Yet older adults rely on them, no?

Older adults, people using mobility aids, people with low vision/acuity, people nursing injuries, on crutches, pushing prams, carrying packages, with toddlers, the list is long of people who are less than fleet of foot. Notwithstanding the fact that our system of driving was designed by, for, and of middle age white men, let’s focus on accessibility.

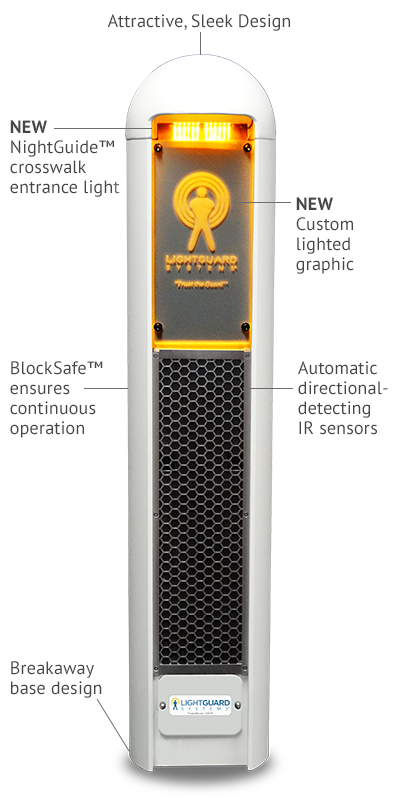

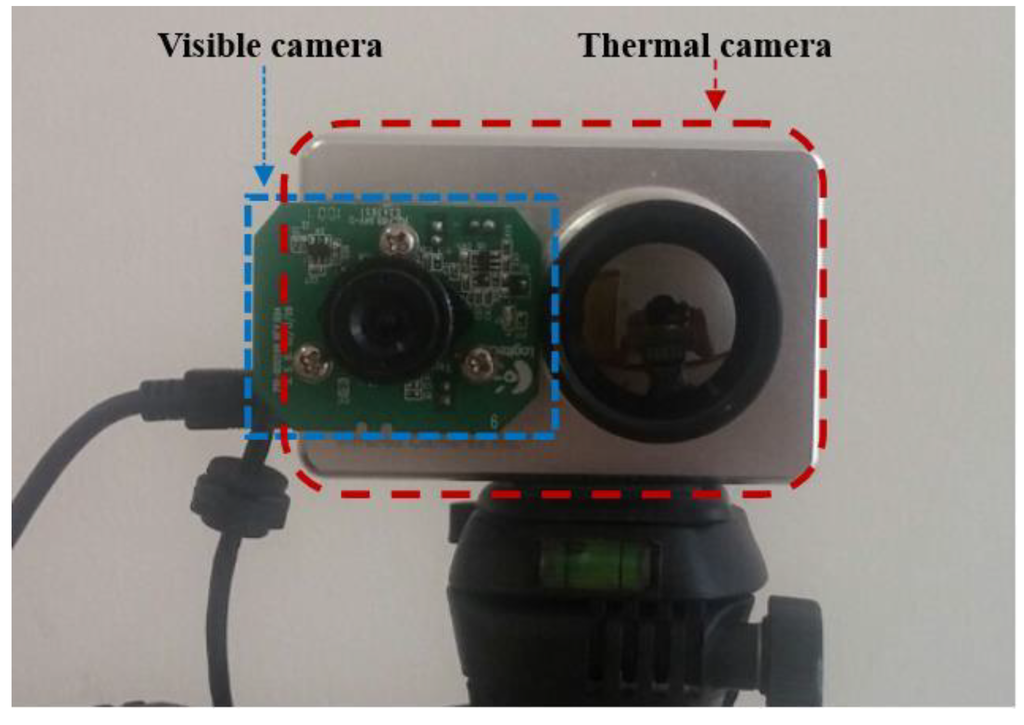

There is an entire industry devoted to making beg buttons better. We have tactile, infrared and microwave detection, audible signals, little signs, countdown signals, and so on. Since the Americans with Disability Act of 1990, essentially every signal in the USA is supposed to be made accessible. I proffer no dissent with this requirement, my issue is that accessible does not equal safer. A 9-lane road may be made “accessible”, but it’s still a really long way across the street. Try that with a walker.

Q - We’ve heard stories about the pace at which lights change, making it difficult for older walkers to get across the road before the signal changes.

I know what you mean. Just as you start to cross, the signal flashes DONT WALK thus increasing your anxiety. The reason: the signal timer wants to minimize the amount of red time to the main road. Hence, the WALK signal will be as short as possible. It can be as short as four seconds. Additionally, signals can be timed at 4 feet per second (fps), yet we know that many people walk at 2.5 fps.

Graphic description of pedestrian interval timing, MUTCD.

Q - Let’s talk a little about ways to alter the dynamic where people walking are essentially penalized for walking.

A number of years ago I started working on street design guides. The idea was so much of our public infrastructure had been given over to highways, we needed books on streets. Streets as spaces to be used by all, not just people behind a windshield.

A core tenet is the number of lanes. We generally write that people should have to cross no more than two lanes at a time, maybe three. Wider roads require medians. This, of course, flies in the face of the traffic industry, which holds that more lanes equals a better “level of service” for drivers. Absurdly, we know that more roads simply induces more driving,

Another is to minimize the number of signals - and beg buttons. All traffic signals should be fixed time. Roundabouts make for much safer intersections. I prefer traffic calming, narrower streets, curb extensions, raised crosswalks, and the like. With lower speeds and fewer lanes, drivers go slower, thus they are more likely to yield. And walkers do not have to beg to gain permission to cross the street.

Q - I see we’ve cycled back around to beg buttons.

The canary in the coal mine. Next time you are out and about, push a beg button and see what happens. Count the seconds before you are allowed to walk, if turning drivers yield, and if your great aunt has enough time to cross the street. If not, it is warning that the street and or intersection has not be well designed.

All photos by author, except a noted and LightGuard, thermal camera, braille signal, audible signal.